A Mother’s Heart in the Shadow of the Cross

Every believer knows what it is to suffer. Illness, loss, betrayal, exile, or grief—these are part of the human condition. Yet in the mystery of salvation, no one suffered in closer union with Jesus than His own Mother. The Catholic Church, for centuries, has turned its gaze toward Our Lady of Sorrows, the Virgin Mary in her deepest suffering, to understand how love and pain can exist together without destroying faith.

When we contemplate Mary’s sorrows, we do not glorify pain for its own sake. We honor the strength of a woman who loved her Son so much that she stood by Him through every blow, every humiliation, and even death itself. Her tears are not only for Christ, but for the whole world that crucified Him—and for each of us when we suffer. To walk with Our Lady of Sorrows is to discover a faith that endures when hope seems lost, and to see how God transforms mourning into redemption.

Who is Our Lady of Sorrows?

The title “Our Lady of Sorrows” (Latin: Beata Maria Virgo Perdolens) refers to Mary in her role as the suffering Mother of Jesus. Unlike images of the joyful Madonna and Child, here Mary is portrayed with her heart exposed, pierced by seven swords. These seven swords represent the seven sorrows of her life, moments when her soul was wounded by pain but remained steadfast in faith.

The Church does not invent these sorrows—they flow from Scripture itself: Simeon’s prophecy, the flight into Egypt, the loss of the boy Jesus, Mary meeting Christ on the road to Calvary, His crucifixion, His lifeless body in her arms, and His burial. Each sorrow is rooted in biblical history and Christian meditation.

Historical Roots of the Devotion

The devotion to Our Lady of Sorrows grew in the 13th century, promoted especially by the Servite Order (the Servants of Mary), founded in Florence in 1233. These seven holy men were moved to spread devotion to the Virgin’s sorrows as a way of calling Christians to repentance and deeper compassion.

In 1817, Pope Pius VII extended the Feast of Our Lady of Sorrows to the whole Church in thanksgiving for his release from Napoleonic imprisonment. Today it is celebrated on September 15, the day after the Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross, to show that the Mother’s suffering is inseparable from the Son’s sacrifice.

The Seven Sorrows of Mary: A Path Through Suffering

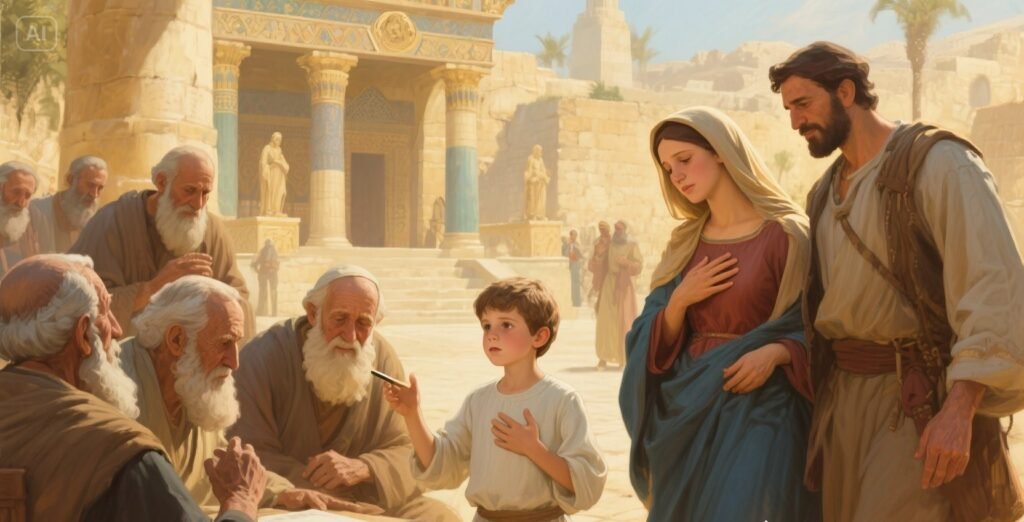

1. The Prophecy of Simeon (Luke 2:25–35)

Mary brings her newborn Son to the Temple with joy, offering Him to God. But the joy is pierced by Simeon’s words: “This child is destined for the fall and rise of many in Israel… and a sword will pierce your soul too.”

This sorrow was not something Mary saw—it was told to her directly. It was a prophecy she carried in her heart, a shadow over every future joy. Spiritually, it teaches us that faith means accepting the Cross even before we see it, trusting God’s plan even when it frightens us.

2. The Flight into Egypt (Matthew 2:13–15)

In the dead of night, Joseph awakens Mary: Herod seeks to kill the Child. They flee as refugees into Egypt. Mary suffers the fear of exile, the insecurity of being hunted. Spiritually, this sorrow shows us how to trust God when forced into unwanted change—to move quickly when the safety of loved ones is at stake, even without answers.

3. The Loss of the Child Jesus in the Temple (Luke 2:41–50)

Mary and Joseph search three days for their twelve-year-old Son. The anxiety of a parent who cannot find their child is almost unbearable. When they discover Him teaching in the Temple, Jesus gently reminds them that He must be in His Father’s house. Spiritually, this sorrow reveals the pain of God’s hiddenness and teaches perseverance in prayer when we feel abandoned or confused.

4. Mary Meets Jesus on the Road to Calvary (cf. Luke 23:27–31, tradition of the 4th Station)

As Jesus carries His Cross, bloodied and beaten, Mary meets His eyes. She cannot stop His suffering, but she can be present. Her strength is silent solidarity. Spiritually, this sorrow teaches us that love does not always “fix”—sometimes it simply stands with another in their pain.

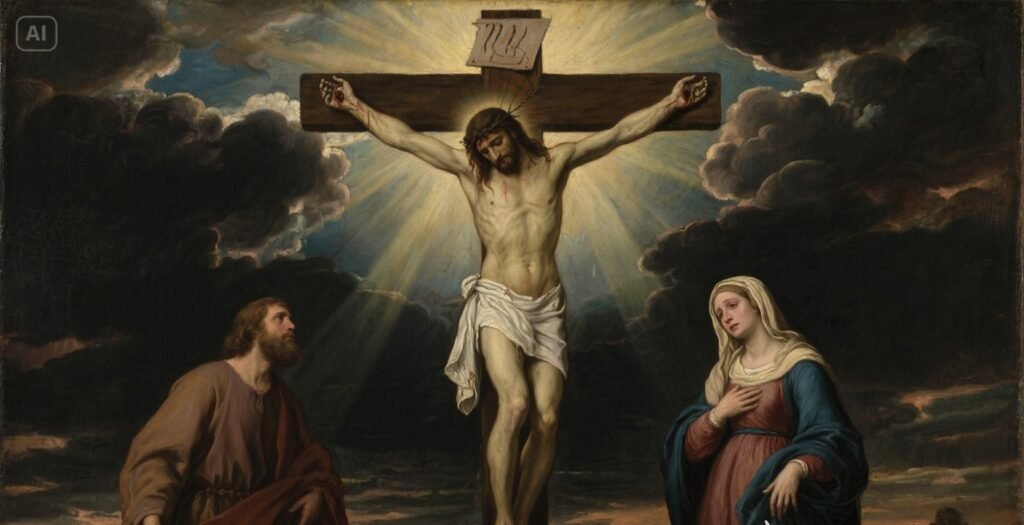

5. The Crucifixion and Death of Jesus (John 19:25–30)

At the foot of the Cross, Mary stands with John and the holy women. Jesus looks down and entrusts His Mother to John, and John to her: “Behold your Mother.” Here Mary’s suffering becomes fruitful—she becomes Mother of all believers. Spiritually, this sorrow teaches that even in the most devastating loss, God is bringing about a larger redemption.

6. Jesus is Placed in Mary’s Arms (the Pietà, cf. John 19:38–40)

Though Scripture is silent on whether she held Him, the Church has long contemplated the Pietà: Mary cradling her Son’s lifeless body. Here grief and love meet in one unbearable embrace. Spiritually, this sorrow reveals that mourning is not weakness but the final act of love—holding close even when all seems lost.

7. The Burial of Jesus (Luke 23:55–56; John 19:41–42)

The stone seals the tomb. Mary faces the silence of Holy Saturday—the world without Christ. Yet her faith does not collapse. Spiritually, this sorrow shows us how to wait in hope when nothing is visible, trusting in God’s promise even in the dark.

The Spiritual Meaning of Mary’s Sorrows

Each sorrow is more than a memory—it is a mirror of our lives.

- Simeon’s prophecy → when life brings hard news.

- Flight into Egypt → when we face exile, sudden change, fear.

- Loss in the Temple → when God feels absent.

- Way of the Cross → when loved ones suffer and we can only stand by.

- Crucifixion → when death and injustice seem to win.

- Pietà → when we mourn the loss of someone we love.

- Burial → when we wait in silence for God to act.

Mary shows us that suffering does not have to destroy faith. In her, sorrow becomes compassion, grief becomes intercession, and loss becomes a bridge to hope.

How to Honor Our Lady of Sorrows

The Chaplet of the Seven Sorrows

This devotion, promoted by the Servites, is prayed on a special rosary of seven groups of seven beads. Each sorrow is meditated upon with 1 Our Father and 7 Hail Marys.

- Begin with the Sign of the Cross and an Act of Contrition.

- Announce the first sorrow (Prophecy of Simeon). Pray 1 Our Father + 7 Hail Marys.

- Repeat for each sorrow.

- Conclude with 3 Hail Marys in honor of her tears.

This can be prayed daily, weekly (especially on Fridays), or as a novena leading up to September 15.

The Stabat Mater

The Stabat Mater is a medieval hymn beginning “Stabat Mater dolorosa, iuxta crucem lacrimosa” (“At the Cross her station keeping, stood the mournful Mother weeping”). It is often sung during Lent or on the Feast of Our Lady of Sorrows. Reciting or singing it is a way of entering into Mary’s grief and love at Calvary.

Other Practices

- Attend Mass on September 15, the Feast of Our Lady of Sorrows.

- Light seven candles at home, one for each sorrow, and pray for those who suffer.

- Wear the Black Scapular of the Seven Sorrows (Servite tradition).

- Perform works of mercy in her honor: visiting the grieving, comforting the suffering, supporting refugees.

- Create a prayer corner with an image of Our Lady of Sorrows, a crucifix, and seven small candles or roses.

Iconography and Symbols

- Seven Swords Piercing the Heart: Represents the seven sorrows, the fullness of her suffering.

- Dark Garments: Black or deep blue symbolize mourning, humility, and faithfulness.

- Roses with Thorns: Symbolize beauty entwined with suffering; red roses for love, thorns for sacrifice.

- The Pietà: Mary holding the dead Christ embodies ultimate compassion and grief.

Conclusion: Sorrow Transformed into Hope

Our Lady of Sorrows is not only the Mother who wept at the Cross; she is the Mother who now comforts every wounded heart. Her sorrows are not just history—they are living prayers for each of us who suffer.

When we meditate on her seven sorrows, pray her chaplet, or honor her feast, we stand with her beneath the Cross and discover that sorrow, united with Christ, always leads to resurrection. Mary’s pierced heart is not a symbol of despair—it is the doorway to unshakable hope.